4. The

Tribute of the Nations - East Wall . ( Plates 37 comprising Plates 38 to 40,

and 47 ) .

The scene on this wall not only is new in kind and

manifestly records an historical event, but a descriptive note and a date are

appended to it . The one, it is true, is brief and very bald, and the other too

broken to be reliable ; but fortunately there is in the adjoining tomb a

second, though very differently treated version of the same or a similar

occurrence, the dating of which is clear, and agrees with what remains of the

numbers here . The inscription is as follows :— " Year [ twelve, second

month of the winter season, eighth day ] of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt,

living on Truth, Lord of the Two Lands, Nefer-kheperu-ra, Son of the Sun,

living on Truth, Lord of [ Diadems ], Akhenaten, great in his duration, and the

great wife of the King, his beloved, Nefertiti, living for ever and ever . His

Majesty appeared on the throne of the Divine and Sovereign Father, the Aten,

who lives on Truth ; and the chiefs of all lands brought the tribute .....

praying favour at his hand (?) in order to inhale the breath of life . The

inscription in the tomb of Huya records the event as the bringing of tribute

from Kharu and Kush ( Syria and Ethiopia ), the East and West, and the islands

of the sea " ; a description probably more rhetorical than exact .

The scene is cleverly set out. The King, drawn to a large scale, sits

enthroned in the middle of the picture, accompanied by his family . On the

right the tribes of the South ( Plate 38 ), on the left the nations of the

North ( Plate 39 ), approach the platform humbly . The dado ( Plate 40 ), shows

the foreground — the crowd on this side of the pavilion . The canopied platform

on which the King sits to receive the gifts is similar to several shown on

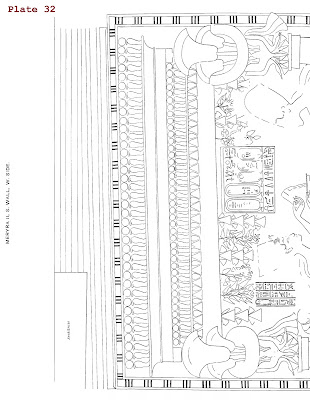

these tombs, and yet cannot be identified with any of them ( Plates 32, 31-a

and 14-a ) ; for the light columns here are as unique as those on the south

wall ( Plate 32 ) . They carry a triple capital, formed by the papyrus, the

lotus (?), and the lily, superimposed one upon the other in an ungraceful

combination . The royal pair sit on cushioned chairs side by side, with their

feet resting on double hassocks . Even at this public appearance before men of

foreign nations their attitude to one another is still most amatory . The Queen

has her right arm thrown round her husband's waist, and her left hand reposes

in his . So much is perceptible ; but the bodies of both have been almost

erased from the hips upwards in ancient time . As usual, all but the bare

outline of the farther figure was covered by the nearer .

Six princesses are shown, a number greater than is

found elsewhere . The new comers are Nefer-neferu-ra, whom we have already seen

on the south wall, and Setep-en-ra . The pretty groups have been injured by

time and ruined by thieves, but the names and attitudes are preserved in

several earlier copies and squeezes . Meketaten turns her head to her sister,

and so shows us the side without the hanging lock . Attracted by the smell of a

persea-fruit ( pomegranate ? ) which Ankhes-en-pa-aten is holding to her nose,

she is stretching out her hand for another which is in her sister's right hand .

Nefer-neferu-aten seems to be holding up a tiny gazelle, and her sister behind

has a similar pet on her right arm, which Setep-en-ra is tickling . Both hold

flowers in the other hand . The different ages of the children is not indicated

by their height or demeanour . As Setep-en-ra does not appear on the south

wall, it may be that she was born during the decoration of the tomb, about the

fourteenth year of the reign . Three nurses of the children stand by the side

of the platform .

The titulary of the sun above contains some

indecipherable additions to what is usual ( perhaps " in the great desert

of Akhetaten " on the left ) .

In front is depicted, in six registers, the bringing

of gifts by negro tribes of the South, and though the picture does not convey

the idea of a spontaneous and unforced payment of tribute, this may be a

mistaken impression . In the topmost register are specimens of the gifts . On

native initiative and artistic impulse, apparently, the tribute of the South

was wont to be made more presentable by the inclusion of set pieces, which were

sometimes very complex and even, in a barbaric way, picturesque . One of the

commonest and simplest methods was to decorate a yoke with skins and tails of

animals, and with rings of gold suspended in long chains or sewn on a

foundation of skin or cloth . These hung from the yoke, while a row of ostrich

feathers adorned the upper side . One such pole is seen resting on a stand, and

two others are being borne by negroes .

A second trophy, of which an example is seen here, takes the form of a

representation of the dom palm, presumably in

precious metal . It is set in a basket, but here the blocks ( ingots of silver

? ) instead of being built into an elegant pyramid are merely placed in two

rough piles . Behind these trophies are seen trays holding ingots (?), bags of

gold dust, and rings of gold ; also shields, bows, and arrows, &c . Below,

similar gifts are being presented by negro chiefs, from Wawat or Mam in Ethiopia,

to judge by their dress ( Plate 35 ) . Ivory, and the eggs and feathers of the

ostrich, form part of the tribute, and the Egyptian love of animals is

gratified by the inclusion of tame leopards, a wild ox (?), and an antelope (?)

.

In the third and fourth registers we see prisoners

taken in a raid, or perhaps slaves as a natural item of the tribute . About a

dozen male negroes are being dragged forward by ropes tied round their necks

and fettering the wrists also . Half that number of women are being led in the

same way, except that their hands are left free . Each is accompanied by three

or four children, the elder ones led by the hand, the youngest one or two

carried in a pannier which rests on the back, but is supported by a band

passing round the forehead . This seems to have been a custom general among

several tribes .

The next register exhibits a war-like scene, but as

weapons are absent, it is to be interpreted as a series of athletic exercises

by the troops, who show their prowess in this more pacific form . The sports

are of three kinds, wrestling, singlestick, and boxing . In the first

competition, two out of the eight combatants have thrown their men, who lie

helpless on their backs as dead . Two of the contests are still being

stubbornly disputed, though the victors can be easily foretold . The execution

of these scenes is very rough, but their vigour is unmistakable . There are

only two rivals in the fencing, and one of them has already received a decisive

blow on the head . Of the three sets of boxers, one pair is still struggling

for the victory, but the victors of the other rounds are already jumping for

joy and loudly proclaiming themselves .

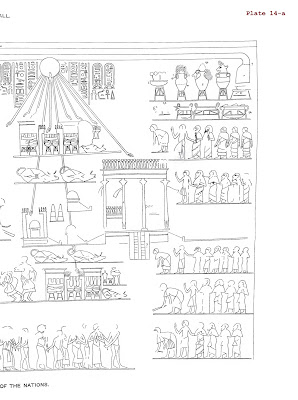

Meanwhile Meryra (?) and four other officials are humbly ascending the

platform to present themselves to the King . They are followed by their shade

and fan-bearers, and by others who may be a select body of the troops which

took part in the expedition, or formed the escort to the mission . In the midst

the street boys give unrestrained expression, after the manner of their kind,

to their delight at the whole proceedings ( Plate 14-a ) . A little group also

shows proleptically the intended decoration of Meryra with the double necklace .

Honours appear to be reserved for his companions also ; for as many necklaces

are displayed on stools, and the closed coffer may also contain something more

in the way of reward .

On the left of the platform ( Plates 39 and 47 ) the peoples of the

North ( our East ) are seen . Those in the six registers immediately behind are

evidently Syrians, to whom the Egyptians applied the loose term Retnu . Nearly

all have the bushy hair and full beard, and the robe wound in several turns

round the body from ankles to neck . Some, however, have the head shaven,

though the beard is long ; — a type which Professor Petrie classes as Amorite .

At the top of the picture we see a large part of the

gifts grouped, consisting of those weapons of war which their Syrian campaigns

had taught the Egyptians to prize and use . There are bows and quivers (?),

falchions and daggers (?), spears, shields, coats of mail (?), and a chariot,

with its two horses. Beneath, we see other presents in the hands of men of the

Retnu . Three young girls who form part of the tribute are pushed forward in

front, as likely to win favour for the rest . The kneeling figures in this and

succeeding rows show, no doubt, the leaders of the embassy . Among the gifts

here are a metal vase, a casket, an elephant's tusk, a bow and arrows, and

three animals, an Antelope, an Oryx, and a Lion . In the next row nine captives

or slaves are led forward by Egyptians : their hands are fettered by handcuffs .

The two vases shown here may have had ornamental covers ( Hay credits the

shorter with a panther's head ), but the state of the wall prevents the exact

forms of the vessels on it being ascertained with accuracy .

The next register seems to show a separate deputation,

perhaps from the land of the Amorites . Their gift comprises two maidens, a

chariot and pair, and various vases of fine workmanship, including a mounted

trophy with the head of a lioness on the lid . The lower two registers may show

still another tribe of the Retnu, but there are no means of distinguishing it .

Their gift consists chiefly of vases in fine metal work . Besides these, there

are two antelopes, and a file of slaves, including women and children .

The enumeration of the tribes of the north who

presented tribute at this time is continued in the long registers below, perhaps

with this difference, that there is no longer any show of force, but a much

greater likeness to embassies of peace .

In

the topmost of these three rows ( Plate 40 ) a small deputation of seven men is

seen, who are clothed simply, and much after the Egyptian fashion . Their

offerings are of an equally simple nature, and clearly from a fertile, but not

a manufacturing land . There are calves ( or calf-shaped metal weights ), piles

of grain or incense shoulder-high, which two men are measuring up, and precious

metal (?) formed into a flattering imitation of the two characteristic Egyptian

structures, the pyramid and the obelisk . It seems certain from these offerings

that they are sent from the land of Punt, its people being grouped here with

the northerners as a non-negro race .

The next embassy is as plainly that of a desert

population. The eggs and feathers of the ostrich are all they have to offer .

Their flowing, open mantle, and the side-lock, and the feather in the hair

proclaim them to be Temehu or Libyans .

While the dress of the remaining nation marks it out

as Syrian, the queue into which the hair is drawn behind indicates the

formidable Kheta ( Hittites ? ) of the distant north . So far, however, from

appearing as members of an invading horde, the elaborate and tasteful

metal-work which they have to offer, as rich no doubt in material as in form,

betoken the highest civilization .

When we seek a more definite origin for these vessels

by a comparative study of the metal-work of Syria we find it a difficult task,

though vessels of similar types are often seen on Egyptian monuments . They are

generally attributed there to the Retnu, a term which at its loosest could

cover all Syria ; for to the Egyptians, as to us, these racial names were

largely only rough geographical distinctions . The vase, adorned by a bounding

bull, as well as that in which the full-faced head of a bull with a disc

between the horns forms the cover, is seen in the tribute of Ramses III at

Karnak, where they are attributed to the Retnu . Hittites, however, are seen to

be included there under this name . In the tomb of Rekhmire at Thebes, where a

more careful classification is to be looked for, the finely-chased vases with

richly ornamented rims are put in the hands both of the Keftiu ( Cretans ? )

and of the Retnu ; but the use of animals, or animals' heads, as ornaments, and

the more elaborate creations, are assigned to the Keftiu . Amongst them are

pieces which are almost duplicates of the heads of the ox and the lioness found

in our picture . The long-necked lipped jug here brought by the Kheta is

carried both by Keftiu and Retnu elsewhere .

Where, then, was the centre of this cultured

manufacture ? The answer may be supplied by a scene in a Theban tomb, where the

chiefs of the Kheta, the Keftiu, Kadesh and Thenpu ( probably Tunip, a city

which in Akhenaten's time was in the hands of the Kheta ), are presenting vases

very similar to those shown here . " A sculptor " follows the chief

of Tunip, carrying a piece of plate . He wears the dress of the Keftiu, and

most of the men who follow, bearing vases, are of the same nationality . A few

resemble in face and dress " the chief of the Kheta " there shown ;

but he does not show the peculiar Hittite face or garb . From this and other

evidence we might gather that the country of the Keftiu was the home of the

craft, and that the neighbouring nations, the Hittites, Retnu, and others

imported these splendid products, and perhaps even learned to imitate the less

elaborate forms ; so that it was as much by their agency as by direct trade

with the Keftiu that they were introduced into Egypt . The recent discoveries

in Crete render this hypothesis extremely likely by pointing to that island as

the home of the Keftiu .

There is no reason, then, why such vases should not be

found in the hands of the Kheta, though it is just possible that our artist has

erroneously drawn Hittites for Keftiu ; for the Hittites, by reason of

distance, are less likely to have sent tribute, and while they are not named or

seen in the tomb of Huya, the people of " the islands of the sea "

there named are not depicted .

The remaining groups on the wall do not form part of

the embassies, but are Egyptian . Below, i.e. on this side of the royal pavilion,

is ranged a large body of troops. The six men drawn up in line in front show,

perhaps, the number of files, but of these only two are actually depicted .

They are curiously armed . Some men of the first file are dressed in the short

tunic of the Egyptians, and carry a long staff curved at the upper end, and a

battle-axe . Two feathers are worn in the hair . Others wear a longer tunic and

carry only a javelin or curved staff . The hair is worn short and a ribbon

attached to the back of the head. The men of the second file carry a spear and

a hooked staff alternately .

The two palanquins of the King and Queen rest beside

the platform . They take the form of state-chairs, each of them carried by two

strong poles . Sphinxes bearing the head and crowns of the King of the two

Egypts ( the Upper and the Lower Egypt ), serve as arm-rests, and the chair is

guarded on each side by the carved figure of a walking lion . The floor on

which the creature stands is attached to the poles before and behind by a uaz column, and, in the King's larger chair, by the figure of a kneeling

captive also .

Here we meet also the personal attendants of the King,

his censing priest, his servants, whose backs are loaded and hands full of all

that he may call for, and the police . The two royal chariots wait in front of

the platform, gaped at by a little crowd . Here also is the military escort,

and several servants who bring forward, for sacrifice or feasting, bouquets,

fowl, and three stalled oxen, whose misshapen hoofs show their fat condition .

Although it is given the aspect of a payment of

tribute in due course, the depiction of the scene in these tombs alone shows

that it was extraordinary, and that its presence here is much less due to any

part Meryra or Huya had in it than to the stir which it caused . It may have

been that missions from such widely separated regions as Coele-Syria, Ethiopia

and Punt met by chance in Egypt, and that the opportunity was taken for a

parade of Egypt's greatness . Or, late as it was, it may have been the first

time that Akhenaten was able to convince the nations that he was firmly seated

on the throne of his fathers, and to arrange an exhibition of loyalty . Or, not

unlikely, it was the result of timely military demonstrations on the North and

South frontiers . The promptitude and the liberality with which the tribute was

paid by many tribes probably always depended on such significant hints . Even

if we regard the prisoners in these scenes as slaves, not captives of war, the

military sports suggest that there had been some such expedition on the South

frontier at least . But whether the inducement to bring tribute was more

warlike or diplomatic, Meryra seems to have taken a leading part in it . Some

unnamed official at any rate is being rewarded, and we may hope that Akhenaten

had this excuse for making a political event so prominent in the eternal house

of his servant .

5. Meryra

rewarded by King Se-aa-ka-ra - North Wall : East side . ( Plate 41 ) .

The unfinished picture on this wall seems to reflect

the troubles which gathered round the new capital in the later years of the

reign or upon the death of Akhenaten . Hastily executed, or left in the rough

ink-sketch, the figures of the King and Queen, with the familiar cartouches of

Akhenaten and Nefertiti replaced by those of Merytaten their daughter and her

husband, Ankh-kheperu-ra, the interrupted project speaks of events, actual or

menacing, in which leisured art could have no place . It is somewhat difficult

to decide whether the design as well as the cartouches belong to Se-aa-ka-ra's

reign, and whether, therefore, these figures represent Akhenaten and his wife

or their successors on the throne . In the absence of sufficient grounds of

suspicion, we must assume that the whole belongs to the reign, or at least to a

co-regency of the new King . Yet it is not obvious why not even one small

design should be completed by him, or why the sun and the royal pair should be

left untouched . The cartouches seem somewhat large and clumsy in comparison

with the rest of the inscription, but the execution of the whole also is very

different from that of the other walls . ( We cannot object to there being two

scenes of the rewarding of Meryra ; because that occurs in the neighbouring

tomb, and there is, therefore, even a presumption in favour of it ) . It might

be put forward as a plausible theory that the King's sculptors were called away

to work in the tomb of Meketaten, and returned later to complete the scenes . But

the execution of the work coincided with an illness of the King, which

threatened to prove fatal, and under the circumstances the royal cartouches and

figures were not proceeded with ; then, when the apprehension concerning the

King was justified, the cartouches of his successor were hastily inserted as a

date ; though events, or the disinclination of the new King, stopped any

further progress with the tomb . The burial shafts were never made, and

Meryra's hopes of a splendid interment here shared the general ruin . The

roughly sketched figures of the King and Queen, the ink of which is now almost

invisible, stand under the radiating sun in the centre of the picture . Behind

them is the palace and before them their faithful palace official, with his

friends and attendants . A part of the group has been removed by the formation

of a recess here at a later date . Meryra is standing on a stool, or up borne

by his friends with officious care, to receive the guerdon of golden necklaces

from the king . His breast is already covered with these marks of royal favour

; and it was no doubt a wise proceeding on the part of the new monarch to make

sure of the devotion of an official so influential in the royal harem .

Part ( 13 ) .. Coming SoOoOon .....

Uploading ..... ↻

Follow us to receive

our latest posts, Leave your comment and Tell your friends about our Blog ..

Thank you ☺☺

No comments:

Post a Comment